2025 Lessons, 2026 Insights

2026 trends and insights

Gallery closures. Against an increasingly turbulent geopolitical landscape, galleries closed worldwide in 2025 leaving artists without representation and needing to recover sales proceeds and unsold works, often in overseas jurisdictions. Collectors found themselves without works they had paid dealers for and in dispute with liquidators and artists over title. Alongside closures, galleries have cut outright or reduced stipend payments to artists and estates leading to at least one artist-gallery dispute (see below). To their credit, some departing dealers have paid their debts and returned works but this has not been the experience across the board and in 2025 we advised a number of artists dealing with liquidators and third-party storage companies to recover unsold works. Since more galleries will likely close in 2026, we recommend artists, collectors and their advisors alike investigate a dealer's financial position carefully ahead of new consignments and purchases and ensure written contracts are in place which anticipate the risk of gallery insolvency.

AI and Contemporary forgeries. Several paintings have recently circulated on the secondary market falsely claiming to be "early works" of a leading contemporary artist born in the 1980s who lives and works in London. We understand these include deliberate forgeries as well as works created by other artists with similar names. Some of the works were said to have been purchased directly from the leading artist’s studio, received as gifts, or even found. Master forgers such as Wolfgang Beltracchi have always been a problem for the art market, but it is unusual for them to target living artists for obvious reasons. As AI copyright litigation continued apace in 2025 and initial decisions were handed down by courts around the world, AI technology’s ability to learn and replicate an artist's style and brushstrokes may be exploited by forgers to create convincing counterfeit works by living artists using their materials of choice. Artists who maintain meticulous studio records of all works will be well-placed to cross-check and establish with confidence whether a specific work did or did not originate from the studio. In time, such records will also become an invaluable resource to protect an artist's market against forgeries post-mortem and prepare a future catalogue raisonné. Collectors, institutions, auction houses and their advisors should be mindful of this emerging forgery risk with contemporary works and verify provenance with care. Buyers may consider taking specific contractual warranties from sellers on a case by case basis.

UK Supreme Court. Photo credit: UK Supreme Court.

Public access in UK litigation. 2026 sees increased public access to key litigation documents in the interests of open justice. Following a landmark 2019 ruling by the UK Supreme Court that all documents placed before a judge and referred to by any party in open court must be available to the public unless there is a compelling reason otherwise, "Public Domain Documents" including witness statements and documents "critical to the understanding of the hearing" will be automatically available on the public-facing side of the court's CE-File filing system starting on 1 January 2026 under a 2-year pilot. This will bring the UK closer to the US, where art litigation is far more common and extensive documentation including correspondence between the parties is routinely available online to anyone who cares to look. Easier access is likely to increase press scrutiny and may encourage settlement where parties are concerned about the court of public opinion. Parties wishing to preserve privacy may seek alternative dispute resolution such as arbitration and mediation which are confidential in nature.

Art disputes. We closely monitor art disputes worldwide. In the US, leading artist Jeffrey Gibson settled his claim against dealer Kavi Gupta over the alleged non-payment of sale proceeds earlier this year, as did artist Deborah Roberts against fellow artist Lynthia Edwards. In the UK, artist Chris Levine has been sued again over his ethereal images of the late Queen Elizabeth II, this time by the artist-holographer Rob Munday with whom he worked without a written agreement. Munday claims he is the joint author of the works and entitled to be identified as such whenever they are published commercially, exhibited in or communicated to the public. London’s National Portrait Gallery attributes one work in its collection to both men but we understand Levine considers himself to be the sole author. Munday also argues that Levine's "lurid neon and fluorescent" versions are a derogatory treatment of his "dignified" originals which infringe his moral rights.

The Levine case recalls recent claims against Maurizio Cattelan and the Estate of Martin Kippenberger in France and Germany by collaborators seeking joint authorship of key works, and the Berlin Court's 2023 ruling that artist Goetz Valien who executed a Kippenberger work is a joint copyright author entitled to the full economic and moral rights that authorship entails. The Kippenberger Estate appealed but their appeal was rejected in December 2025, confirming Valien as co-author. These cases are a timely reminder that artists and their dealers can and should require all freelance collaborators, designers and fabricators with any creative freedom to sign documentation addressing both copyright and moral rights in future works at the outset of any collaboration.

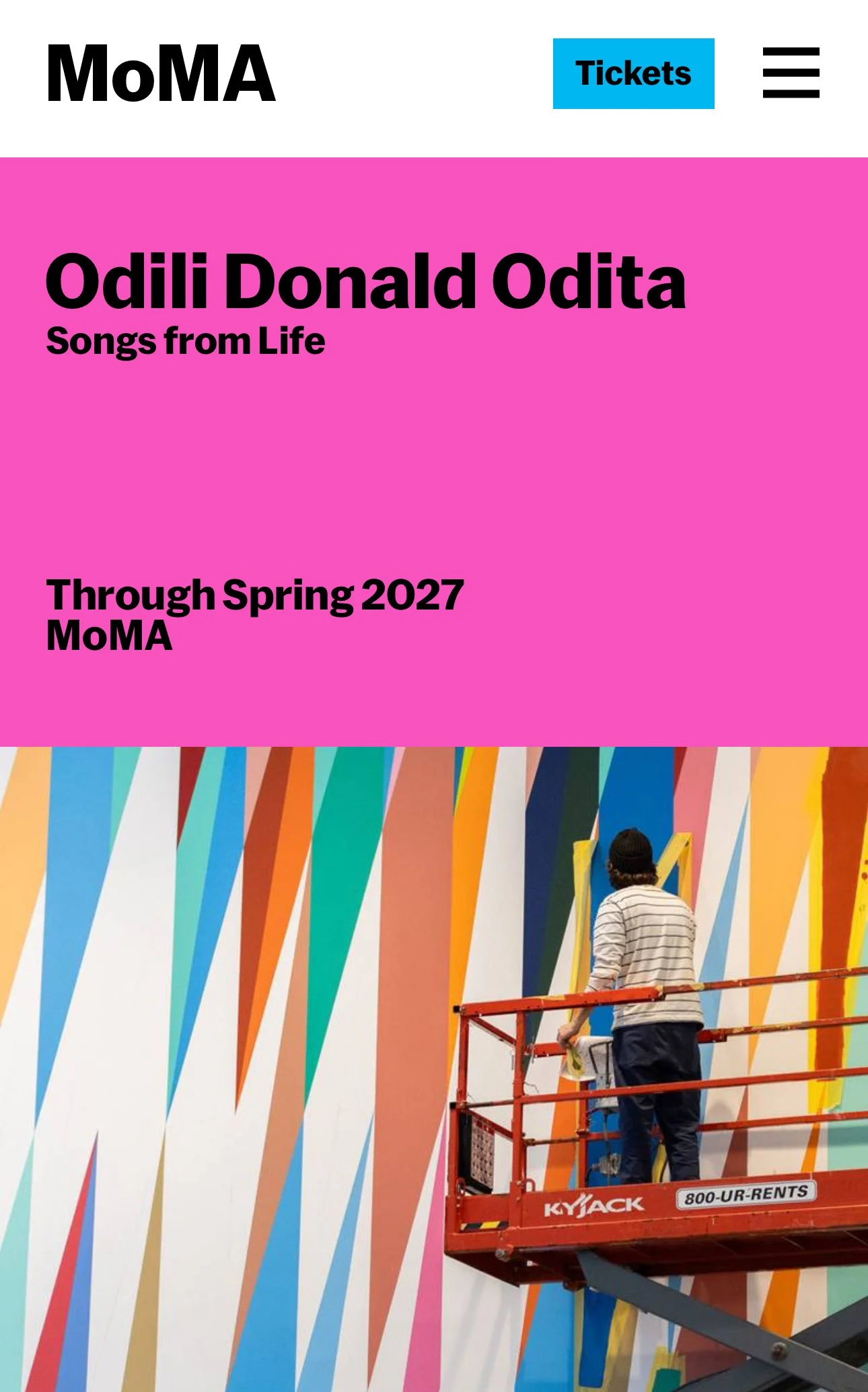

US artist Odili Donald Odita, whose large-scale commission fills MoMA's lobby through spring 2027, sued Jack Shainman Gallery (JSG) in New York in October 2025 seeking the return of consigned works. Having collaborated for almost 20 years, JSG paid the artist a monthly advance of at least $14,000/month pursuant to a Letter of Agreement from late 2016 until October 2024 when it said the artist owed $586,000 and froze payments pending repayment of the balance. Later sales have reduced the balance but the parties disagree over the amount outstanding: Odita says it is around $180,000 and JSG says it is around $290,000). It is unfortunate that the parties could not resolve their dispute privately before sensitive details became public and significant legal fees were incurred.

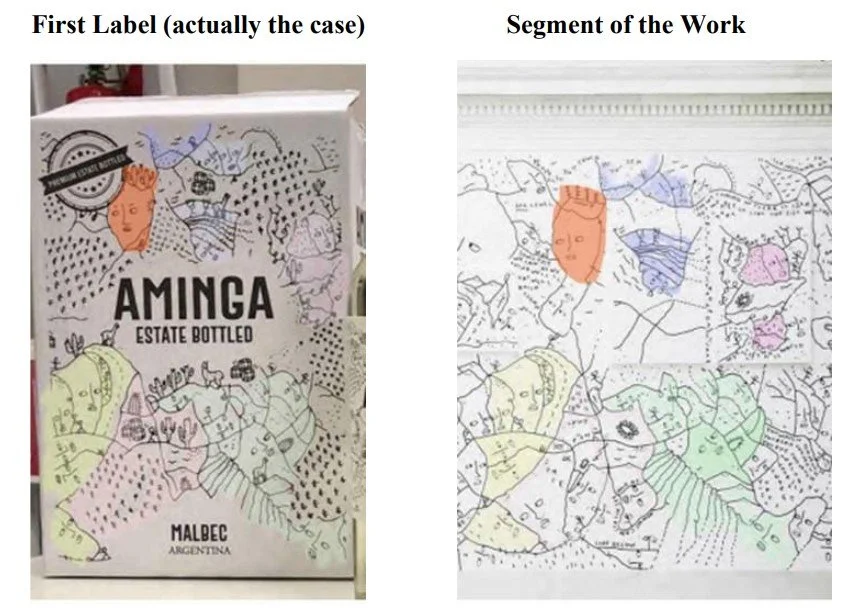

First wine label (L) and Shantell Martin work (R), colour-coded by the claimant artist to highlight copying.

And US-based British artist Shantell Martin had mixed fortunes in her UK claim for copyright infringement against a company which imported wine into the UK bearing labels which copied her artwork. The Court agreed that one early label infringed her copyright but held that two later versions moved sufficiently far away from her original wall drawing to avoid copyright infringement. Since relatively few bottles were sold with the first (infringing) label, the judge indicted Martin's damages would be under £10k. Martin had claimed at least $200k.

Berlin studio visits with the Institute for Artists and Estates.

Estate planning for artists and dealers. The UK tax system has seen major changes since the current Labour government was elected in 2024. UK-resident artists and dealers should be aware of the imminent reduction in so-called "Business Property Relief" (BRP) which will increase the inheritance tax (IHT) payable by artist and dealer estates with business assets worth over £2.5 million at the date of death. Whilst the rules are complex and individual advice should always be taken, BRP has for many years allowed well-advised artists and dealers to structure their businesses such that no inheritance tax (IHT) was due on business assets regardless of their value. After a last-minute change announced on 23 December 2025, 100% BPR will now be limited to the first £2.5 million of business property from 6 April 2026, with business assets above this threshold attracting 50% relief or an effective IHT rate of 20%. Estate planning is vital for all art market participants but particularly so for artists and we were delighted to join the Institute for Artists and Estates in Berlin for a 3-day deep-dive into the subject in September last year which brought together leading market experts with those running or preparing to run significant artist estates.

Public Domain Day. Last but not least, the work of artists who died in 1955 entered the public domain on 1 January 2026 in those countries where copyright lasts for the artist’s lifetime plus 70 years post-mortem. We can expect to see more images and exhibitions of cubist star and pop art forerunner Fernand Léger (1881-1955) as well as Yves Tanguy (1900-1955) and Nicolas de Staël (1914-1955) who are perhaps the most high-profile of the 1955 vintage. Interestingly, Léger signed an exclusive three-year contract in 1913 giving his dealer — Cubist champion Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1884-1979) — the right of first refusal to buy (not take on consignment) his recent works directly from his studios. Léger committed to sell his works exclusively to Kahnweiler, who in return purchased all of the oil paintings and fifty of the drawings he produced each year. Kahnweiler had similar agreements with Braque, Picasso, Derain, de Vlaminck and Gris making him the sole supplier of their Cubist art until the onset of the First World War. Whilst much has changed since then, it is still the case that every generation produces its star artists and dealers — and that they often work and grow together.

Main image above: Yves Tanguy, There, Motion Has Not Yet Ceased, 1945.

This Insight and any information accessed through the links is for general information only and does not constitute legal advice. Please contact us if you need advice on your particular circumstances.

Artist-Dealer disputes: Jeffrey Gibson v Kavi Gupta Gallery

Recent litigation in the New York courts between artist Jeffrey Gibson and former dealer Kavi Gupta Gallery highlights the importance of clear written agreements

Whilst disputes between artists and dealers are not uncommon, most are resolved privately without going to court. The few cases that reach the courts in the UK, US and beyond are usually settled before a court decision is handed down. In May 2023, leading artist Jeffrey Gibson (who represented the US at the 2024 Venice Biennale and joined Hauser & Wirth in October 2024) filed proceedings in the New York courts against the Kavi Gupta Gallery (the Gallery) alleging non-payment of over USD 630,000 in artwork sale proceeds. After 21 months of public litigation, the case settled on 27 February 2025. We consider the claims on each side and the lessons for artists and dealers alike.

Legal Proceedings

According to Gibson’s Complaint [1], he began consigning art works to the Chicago-based Kavi Gupta Gallery in late 2017 with neither party proposing a written agreement detailing the consignment terms. The Gallery paid him on time initially but he became concerned when it fell behind. Gibson began chasing in April 2022, hired a lawyer in December 2022 and felt he had no choice but to file legal proceedings on 8 May 2023 claiming withheld sale proceeds of $638,919.31 [2]. Gibson filed a schedule to the proceedings detailing what he considered were the sale proceeds owed to him for completed sales including “acceptable deductible costs”. For sold works, Gibson’s position was that the Gallery had his authority to deduct framing costs paid by the Gallery “off the top” of the purchase price before allocating the balance 50/50 between the Artist and Gallery; but that no other costs besides framing costs were to be reimbursed “off the top”.

In its August 2023 Answer with Counterclaims, the Gallery claimed it had incurred significant production costs on Gibson’s behalf to fabricate the consigned works and that the artist agreed - as it said was “a well-settled industry standard” - “that production costs and expenses associated with the production of the work would be taken off the top when the particular piece or production was sold… at no time were such reimbursable costs limited to framing ”.

In addition to unspecified production costs, the Gallery went further, claiming it was also entitled to “repayment of all funds expended to build and promote Plaintiff’s [Gibson’s] career” which it said exceeded $786,000 (i.e. more than Gibson claimed in unpaid sale proceeds). The artist filed a schedule of sale proceeds paid by the Gallery from June 2019 to July 2023 which totalled $2,797,576 (suggesting the Gallery had earned at least this amount as its 50% commission from the relationship). According to the schedule, the Gallery paid Gibson over $700,000 from February to May 2023 including $86,500 after Gibson filed the proceedings. The artist noted it would have been against the Gallery’s interests to pay him these funds if it believed its claim for marketing expenses had any merit; and that Kavi Gupta had stated in his affidavit that the oral agreement he believed his Gallery had with Gibson only allowed recoupment of production (not marketing) costs from sale proceeds.

Settlement

In late 2024, the parties completed a session with a court-appointed mediator and informed the presiding Judge Hummel that they were engaged in settlement discussions. Artnet published an article in January 2025 suggesting the Gallery was in financial difficulty [3] and the parties settled their dispute confidentially on 27 February 2025.

Lessons

Like many artist-dealer disputes, there was no written agreement on a commercial point which became contentious: in this case, the treatment of production costs expended by the Gallery [4]. The Artist’s Complaint said: “At no time did the Gallery ever prepare or propose a written contract setting forth any of the terms that would govern the consignment”. Whilst that may be true, artists can and should propose a written agreement if the gallery does not. This is particularly important given the artist’s relative weakness in a consignment relationship where they hand over possession of valuable artworks without payment.

The Gallery’s claim for reimbursement of marketing costs is surprising since such costs are typically borne by the dealer (whether works sell or not). That said, like most jurisdictions, English law leaves parties free to allocate expenses as they wish and well-advised artists and dealers will therefore spell-out the allocation of all costs in a clear written agreement to minimise the risk of dispute.

In terms of production costs, artists and dealers often agree that the paying party will be reimbursed “off the top” of the purchase price before the “net” profit is shared but this is again a commercial question to be agreed in writing. Parties should also decide if and how production costs expended by the gallery will be recovered if a work remains unsold at the end of the consignment period. Is such expenditure a loan which remains outstanding, or an investment which the gallery loses having failed to sell the work and generate a return during the consignment period (the latter seems to have been Gibson’s position in the recent proceedings)? In its 2022 dispute with the artist Diana Al-Hadid, the Marianne Boesky Gallery argued before the New York Courts that it had an ownership interest in a sculpture that it had helped fund over a decade earlier when it represented the artist [5]. In a rare artist-dealer dispute to reach a Court decision, the New York court rejected the gallery’s argument, holding that the consignment agreement did “not confer or transfer an ownership interest in the sculpture” to the gallery. The gallery appealed the decision unsuccessfully [6].

Finally, artists risk being left unpaid if their gallery becomes insolvent after selling and receiving payment for consigned works. To minimise this risk, artists should require their dealers to pay their share promptly upon payment by the buyer and be very mindful of late payments. They should also consider the inclusion of provisions in the consignment agreement to encourage timely payment and improve their position in the event of the gallery’s financial difficulty.

[1] Jeffrey Gibson v K R J S Corporation d/b/a Kavi Gupta Gallery, Case No. 1:23-cv-00557-LEK-CFH, United States District Court, Northern District of New York.

[2] In accordance with § 12.01 of New York Consolidated Laws, Arts and Cultural Affairs Law, Gibson argued that these sale proceeds were trust property (see here).

[3] “The Rise and Fall of Kavi Gupta: Chicago Dealer Faces Lawsuits, Claims of Mismanagement”, Artnet, 9 January 2025 (see here).

[4] Written agreements were similarly missing in Frank Bowling v Hales Gallery Ltd before the English courts in 2020-21; and in Howardina Pindell v N’Namdi Galleries before the New York courts in 2020-22, both of which also settled confidentially (see our earlier reports here).

[5] Art Works, Inc. v. Diana Al-Hadid, New York County Supreme Court, 651267/2021 (see our earlier report here and the court’s May 2022 decision here).

[6] See New York Appeal Court decision dated 6 October 2022 here.

Main image: The Two Fridas, 1939 by Frida Kahlo

This Insight and any information accessed through the links is for information only and does not constitute legal advice. Please contact us if you need advice on your particular circumstances.

Fair Warning: Phillips withdraw lot over resale restriction

Auction house withdraws work and New York court entertains claim that resale restrictions may encumber title

Leading auction houses will in our experience withdraw recently produced (“wet”) paintings from sale when they are put on notice that the would-be seller is subject to a reasonable resale restriction under US or English law which a sale by the house would breach. Under English law, auction houses will be concerned to avoid potential claims and liability for inducing or procuring the seller to breach its contract with the artist or gallery from whom the work was acquired [1].

A recent dispute before the New York courts - DW Properties v Live Art [2] - reveals that Phillips auction house withdrew a lot from sale in April 2023 after it was notified of a resale restriction. The case charts new territory since the Phillips consignor was not itself subject to the restriction in question. The restriction was instead downstream: the party from whom the Phillips consigner acquired the work had arguably re-sold the work to the consigner in breach of a restriction. The Phillips withdrawal, and the subsequent Opinion of the New York Judge, raise the question of whether a downstream resale restriction might – at least under New York law – impact the ability to transfer good title in the work during the resale period.

Background

A collector called Sacha Daskal had sought advice and acquired a number of works from an art trading platform called Live Art. In November 2021, Live Art informed Daskal of an opportunity to purchase a painting by the Ghanian artist Cornelius Annor (b. 1990) titled “ya tena ase” (the “Painting”). Daskal informed Live Art that he intended to hold the Painting for a limited time before reselling it and asked Live Art a series of questions about the Painting’s marketing potential and estimated resale price. According to Daskal, Live Art advised that he could likely resell the Painting for USD 120,000 and represented to Daskal that he would acquire good title upon payment of the purchase price with no mention of any restriction on resale. Daskal acquired the Painting from Live Art through his Belgian company, DW Properties, on 18 November 2021 for USD 80,000 (including a USD 5,000 commission for Live Art) and the invoice between Live Art and DW Properties (see here) included a number of Terms and Conditions which included the second bullet below:

Live Art had acquired the Painting from Good Lamp LLC, a company owned by the entrepreneur and collector Jeremy Larner, a few days prior on 12 November 2021 for USD 75,000. The earlier invoice between Live Art and Good Lamp LLC placed the following obligation on Live Art:

Live Art did not however include these restrictions in its invoice with DW Properties.

After the acquisition, Daskal asked Live Art multiple times if it would be a good time to sell the Painting. In February 2023, Live Art recommended that Daskal consign the Painting to Phillips. According to Daskal, Live Art assured him that he would be able to break even or profit above his USD 80,000 purchase price and Daskal proceeded to consign the Painting to Phillips. On 13 April 2023, Phillips received an email from Good Lamp LLC stating that the Painting “is restricted from going to auction until November 13, 2024, and that it is also subject to a right of first refusal which has not been given to my company Good Lamp.” Since Live Art had not included the restrictions in its contract with DW Properties, Phillips could have advised Good Lamp that because Good Lamp had no contractual relationship (known as privity of contract) with its fiduciary (DW Properties), Phillips would proceed to sell the Painting and Good Lamp’s remedy would lie in a damages claim for breach of contract against Live Art with whom it had a contractual relationship. Phillips however elected to withdraw the Painting from the auction, raising questions and laying the ground for the legal proceedings which brought the matter into the public arena.

Legal Proceedings

DW Properties filed legal proceedings against Live Art before the New York courts on 28 June 2023 seeking damages for Live Art’s alleged breach of contract. DW Properties argued that the resale restrictions in the contract between Good Lamp and Live Art (which Live Art had not passed onto DW Properties) clouded DW Properties’ title to the Painting and amounted to a breach of the warranty of good title which Live Art had given (see above).

Live Art instructed the seasoned and respected art lawyer John Cahill, a former General Counsel of Phillips auction house, who filed a Motion to Dismiss for failure to state a claim (a procedural mechanism by which Live Art sought to dismiss DW Properties’ claims against it at a preliminary stage). Live Art argued amongst other things that DW Properties had confused a “warranty of title” (which Live Art agreed it had been given but said was not breached) with “resale restrictions”; that the resale restrictions between Live Art and Good Lamp had no effect on DW Properties’ title to the Painting; and that its contract with DW Properties contained no warranty concerning resale restrictions.

On 22 April 2024, the US District Judge of the Southern District of New York issued its Opinion and Order largely denying Live Art’s Motion to Dismiss and allowing most of DW Properties’ claims to advance. The Court held that although DW Properties was not a party to the contract between Live Art and Good Lamp containing the resale restrictions, Live Art’s failure to comply with those requirements “may have affected its ability to pass good title to DW Properties”. The Court questioned whether a seller’s breach of a contractual resale restriction might create an “encumbrance” sufficient to invoke section § 2-312(1)(b) of the N.Y. Uniform Commercial Code which implies into all sale of goods contracts a “warranty by the seller that . . . the goods shall be delivered free from any security interest or other lien or encumbrance of which the buyer at the time of contracting has no knowledge”. A similar “no encumbrance” provision is implied into sale of goods contracts under English law: see for example section 12(2)(a) of the UK’s Sale of Goods Act 1979. The District Court opined: “DW Properties’ allegations that Phillips declined to auction the Painting because of Live Art’s failure to comply with the requirements of its contract with Good Lamp suggests that such failure may constitute a continuing encumbrance on the Painting.”

DW Properties and Live Art settled their dispute in principle on 28 October 2024 and the court file indicates that Live Art has agreed to make an undisclosed settlement payment to DW Properties by 31 December 2024.

Comment

There is growing consensus amongst art lawyers not employed by auction houses that contractual resale restrictions will be enforceable under both US and UK law when drafted reasonably and properly incorporated [3]. Prior to the present case, conventional legal wisdom in the US and UK was that whilst a party selling a work in breach of a contractual resale restriction risks liability for breach of contract (typically damages or an injunction to prevent a sale), it was nevertheless capable of transferring title in the work to a buyer; and that the buyer would not be bound by the earlier downstream restriction. The Phillips decision to withdraw the Painting, followed by the Opinion of the New York Judge, raises and leaves open the question of whether downstream contractual resale restrictions are capable of encumbering title in a work under New York law.

It is unfortunate that the case settled with this question outstanding. Since it may be some time before the question is revisited by the US courts, prudent secondary buyers of recently created contemporary art would be well-advised to seek written warranties that the seller (a) did not agree to resale restrictions when acquiring the work; and (b) has no knowledge of downstream resale restrictions which previous owners may have agreed. Those buying by private sale through auction houses and other agents might seek express warranties of both title and the absence of direct and downstream resale restrictions.

For artists and their galleries, the case demonstrates that resale restrictions are taken seriously by both auction houses and the courts and offer a valuable line of defence to speculative “flipping”. And for owners of work subject to primary market resale restrictions, the case opens up a new risk. Those reselling in breach of resale restrictions have always risked claims from the beneficiary of the restriction (the artist or their gallery). A failure to disclose the restriction to the buyer may now expose the seller to a claim from the buyer alleging breach of the seller’s warranty of good title.

[1] For a cogent analysis of the legal risks to the “inducing” dealer or auction house, see Aaron Taylor, ‘Resale Restrictions in the Contemporary Art Market’ (2023) 28 Art Antiquity and Law 275.

[2] DW Properties v. Live Art Mkt., Inc., No. 23-CV-7004 (JPO), 2024 WL 1718688 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 22, 2024).

[3] See, for example, ‘Enforceability and Effectiveness of Art Market Resale Restrictions’, The Art Law Podcast, 8 October 2024; Aaron Taylor, ‘Resale Restrictions in the Contemporary Art Market’ (2023) 28 Art Antiquity and Law 275; Pierre Valentin, ‘The right of first refusal in art sales in New York’, Linked In, 14 August 2024; Adam Jomeen, ‘On the Flip Side: Resale Restrictions under English Law’, Art Law Studio Ltd, 31 March 2023.

This Insight and any information accessed through the links is for information only and does not constitute legal advice. Please contact us if you need advice on your particular circumstances.

Joint Authorship: Whose work is it anyway?

Martin Kippenberger and Götz Valien, "Paris Bar", Variante 3, 1991-2010

Authorship disputes between artists highlight the importance of reaching agreement on copyright ownership at the start of any potentially creative collaboration

With due credit to Marcel Duchamp, the art market is largely willing to accept that a work is “by” the artist who conceived it, regardless of whose hand executed the work itself. Recent authorship disputes involving the work of Maurizio Cattelan and Martin Kippenberger highlight the risk of copyright ownership being shared with collaborators who exercise free and creative choices in bringing the concept to life. Under English law, a work will be a “work of joint authorship” where it is produced by the collaboration of two or more authors and the contribution of each is not distinct. In the leading English case involving the authorship of a screenplay, the High Court noted that trying to separate the contributions of joint authors “would be like trying to unmix purple paint into red and blue.” [1]

Many artists run sophisticated studios employing teams of skilled assistants to develop and realise their work. That will not usually create copyright issues under English law provided the assistants are employed by the artist (or their company) and make works in the course of their employment. Difficulty can however arise where artists collaborate with others on a freelance basis with no employment relationship. This briefing considers two recent disputes in France and Germany which highlight the risk of a collaborator claiming joint authorship of a work after it becomes valuable and art-historically significant.

Götz Valien v Martin Kippenberger Estate

Challenging the notion of the artist as singular genius and sole author, Martin Kippenberger (1953-1997) commissioned a billboard artist in 1981 to realise his "Lieber Maler, male mir" (“Dear painter, paint for me”) concept of large-scale realist paintings based on his own photographs. Today, works from the series can be found at MoMA, the Pinault Collection and the Hasso Plattner Collection. Pinault acquired its work from the first owner at auction in 2006 for £500,000 and Plattner paid USD 6.4M at auction in 2013.

Building on his earlier series, Kippenberger hired a Berlin poster-painting company called Werner Werbung to produce a painting from a photograph he had also commissioned of his exhibition at Berlin’s famous Paris Bar which was and remains a popular meeting place for artists. Werner engaged the artist Götz Valien on a freelance basis to produce “Paris Bar, Version 1” in 1991 and a second version (“Paris Bar, Version 2”) in 1993 based on another photo reference showing “Version 1” hanging in the Paris Bar.

Valien apparently had no contact with or directions from Kippenberger and understood both canvasses were for the owners for Paris Bar. Version 1 hung in the Paris Bar until 2004 before being sold at Christie’s as an artwork attributed to Kippenberger in 2009 for GBP 2.3M. The 1993 version was sold via Phillips auction house in 2007 for £636,000 and is now in the Pinault Collection. After discovering the 2009 Christie’s sale, Valien made a third version of Paris Bar (Version 3) in 2010 which he attributed to himself alone and filed legal proceedings in Munich in 2022 against the administrator of the Kippenberger Estate which manages the artist’s copyright and publishes his catalogue raisonné. Having declined Valien’s request to be named in the catalogue raisonné, Valien’s claim sought to prevent the Estate from exploiting the “Paris Bar” paintings without naming him as a joint author (Case No. 42 O 7449/22).

Contradicting the Duchampian view of authorship, the Munich Court ruled in August 2023 that Götz Valien is indeed a joint author of the various versions of the painting "Paris Bar" alongside Martin Kippenberger pursuant to Section 8(1) of the German Copyright Act and must be named accordingly. Whilst agreeing that Kippenberger had undoubtedly initiated Versions 1 and 2 and made creative choices including the layout of his exhibition in the Paris Bar and the style of the painting (by selecting Werner specifically), the Court held that Valien had had, and had exercised, sufficient creative freedom in bringing the reference photograph to life on the canvas. The Court noted by way of example that the “warm, inviting, lively and radiant” atmosphere in Version 1 was neither present in the reference photograph (shown below) nor directed by Kippenberger with whom he had no contact.

Reference image by Gunter Lepkowski

Valien had also signed the canvas of Version 1 in his own name, invoking the rebuttable presumption of authorship contained at section 10 of the German Copyright Act (a similar presumption exists under English law at section 104(2) of the UK’s Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988). Responding to a counterclaim by the Kippenberger Estate, the decision prohibits Valien from exhibiting the 2010 version of "Paris Bar” (Version 3) without acknowledging Kippenberger as joint author.

The Kippenberger Estate has filed an appeal which remains pending.

Daniel Druet v Maurizio Cattelan

We first reported on French proceedings targeting Maurizio Cattelan in 2022. Between 1999 and 2006, Cattelan and his gallerist Emmanuel Perrotin engaged the sculptor Daniel Druet to produce eight hyper-realistic wax sculptures which Cattelan incorporated into some of his most famous and highly valued works including La Nona Ora (1999) and Him (2001). Portraying a penitent, child-like Adolf Hitler and currently on display at the Bourse de Commerce in Paris until 2 September 2024 (shown in situ below), the artist’s proof of Him sold for USD17.2M at Christie’s in May 2016 which remains Cattelan’s auction record. Perrotin conceded that they were “naïve” to engage Druet without a written contract which could have addressed the authorship questions now in dispute.

Installation shot of Maurizio Cattelan’s Him (2001) at the Bourse de Commerce in Paris. Photo: Adam Jomeen.

After a fruitless request to be credited as the author of the wax sculptures, Druet filed proceedings in 2018 in the Paris courts against (a) Perrotin; (b) Perrotin’s publishing company, Turenne Editions; and (c) the Monnaie de Paris museum which had exhibited four of the disputed works in 2016/17 without crediting Druet. Druet claimed significant damages plus a declaration that he was the sole author of the eight works into which Cattelan incorporated the wax sculptures. Cattelan was joined to the proceedings by the museum under a contractual indemnity but was not sued as a primary defendant by Druet.

The Paris IP Court rendered its decision on 8 July 2022. It noted that by framing his claim around the names of the artworks, Druet was claiming sole ownership of the final artworks as they were titled, staged and disclosed to the public by Cattelan. It further noted that pursuant to article L. 113-1 of the French IP Code, the person in whose name an artwork is disclosed to the public is the presumptive author. Since all eight contested works were disclosed to the public in Cattelan’s name alone, the Court considered it essential that Cattelan be called as a primary defendant by Druet to assert his alleged authorship. In Cattelan’s absence, the Court ruled Druet’s claims for copyright infringement against the three defendants were “inadmissible”.

Rather than refiling his claim against Cattelan directly for joint (rather than sole) authorship of the eight works, Druet curiously appealed the decision of July 2022. The Paris Appeal Court rejected the appeal almost two years later, on 5 June 2024, agreeing with the trial court that Druet’s claims for copyright infringement cannot be addressed without Cattelan’s inclusion in the proceedings as a primary defendant. The Court affirmed, as a matter of French procedural law, that Cattelan’s presence as a guarantor of the museum’s potential liability was insufficient to create the requisite legal nexus between Druet and Cattelan. The claim therefore failed on procedural grounds before an analysis of Druet’s potential joint authorship was undertaken by the court.

Druet’s legal strategy is hard to understand and was, it seems, Bound to Fail. With the right strategy, our Paris correspondents consider Druet would have had a fair chance of establishing his joint authorship of the eight works. Six years after starting fruitless proceedings, it remains to be seen whether Druet has the energy and resources to pursue his claim against Cattelan directly. Like the Munich court in the Kippenberger case, the Paris court would carefully review Cattelan’s instructions to Druet and the extent of Druet’s creative freedom in realising the wax works. For now, the legal presumption of Cattelan’s sole authorship prevails.

Lessons

Collaborators can agree in advance that copyright in what is to be produced should be owned by a single person or body. Where artists collaborate with third parties to develop or realise their concept, they or their galleries should ensure clear written contracts are in place at the outset of the relationship addressing future copyright ownership and credits. It is noteworthy that the Kippenberger and Cattelan claims emerged after the works sold for significant sums many years after the collaboration. This suggests that the risk of a claim for joint authorship may increase as the profile of the initiating artist increases. Druet’s curious legal strategy certainly reinforces the importance of selecting lawyers carefully.

[1] Martin & Anor v Kogan [2021] EWHC 24 (Ch) (11 January 2021), para 323.

This report and any information accessed through the links is for information only and does not constitute legal advice. Please contact us if you need advice on your particular circumstances.

On the Flip Side: Resale Restrictions under English Law

The Last Supper (detail), c.1515-1520. Attributed to Giampietrino (fl. 1508-1549) and Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio (1467 - 1516). Copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, 1494-1498.

We consider the use of resale restrictions in the contemporary art market and conclude they are capable of being enforceable under English law when drafted correctly

Coming to an Evening Sale near you

The art market’s appetite for increasingly wet paintings continued unabated in 2022 with striking auction debuts for artists including Lucy Bull (b.1990), Anna Park (b.1996) and Lauren Quin (b.1992). Bull’s ‘8:50’ (2020) sold for USD 1.45 million at Phillips Hong Kong; Quin’s ‘Airsickness’ (2021) sold for USD 587,000 at Phillips London; and - with the question on everyone’s lips, perhaps - Park’s ‘Is it worth it?’ (2020) sold for USD 480,000 at Christie’s Hong Kong. And building on a remarkable 2021 in which auction prices passed USD 1 million in June and GBP 2 million in October, the market for British painter Flora Yukhnovich (b.1990) showed little sign of cooling in 2022.

The pricing gap between the primary market (by which we mean the first sale of a new work - either directly from the artist or through their gallery) and the secondary market (every subsequent re-sale) can be striking. Yukhnovich’s large-scale paintings were reportedly priced at around USD 40,000 in 2019. The artist showed new work with the Victoria Miro in March 2022 where the largest works were reportedly priced at GBP 350,000 (USD 470,000). The same month, a work executed in 2020 achieved GBP 2.7 million (USD 3.6 million) at Sotheby’s in London.

Since the goal of artists and their dealers is not usually to secure the highest price but to place work in private and public collections which enhance the artist’s profile and offer the work critical exposure over the long-term, a speculative market presents artists and their dealers with a number of interconnected challenges, not least: deciding the level at which to price new work; deciding who is given primary market access at an effective discount to “market” (if that word captures the price that the highest bidder would be willing to pay); and deciding what mechanisms will be relied on to incentivise buyers to hold the work rather than take it straight to auction.

Contractual Resale Restrictions

One increasingly utilised legal tool - and the focus of this briefing - is the contractual resale restriction which typically restricts the buyer’s ability to resell or otherwise dispose of a work for a specified period. The most common restriction is a “pre-emption right” or “right of first refusal” which usually requires the buyer to offer the work back to the artist or gallery if they wish to resell within an agreed period after purchase (typically 3 to 5 years). Where the gallery acts as the buyer’s resale agent under a right of first refusal, it will earn a commission on the resale which it may have agreed to share with the artist (adding to the limited artist resale right available to certain artists in certain jurisdictions including the UK). [1]

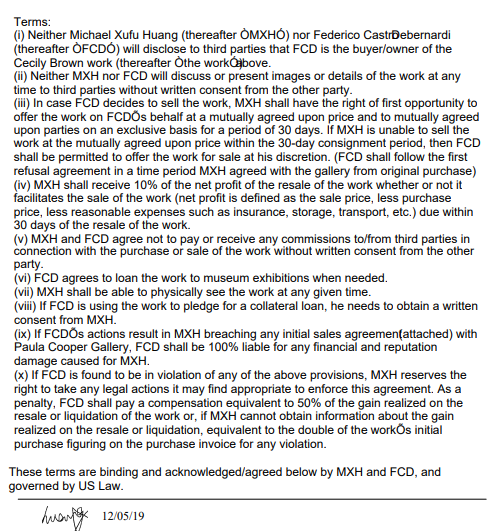

Contractual resale restrictions were at the heart of a recent US dispute between the Paula Cooper Gallery and the high-profile Chinese museum founder Michael Xufu Huang who resold Cecily Brown’s Faeriefeller (2019) in breach of the Gallery’s Conditions of Sale which included a pre-emption right. Huang signed the Conditions of Sale and later filed a copy in Florida court proceedings (see below):

Paula Cooper Gallery’s Conditions of Sale signed by Michael Xufu Huang on 4 December 2019. Filed with the Florida Court by Huang in his claim against Federico Castro Debernardi (Case No.: 2021-005156-CA-01).

The disputes arising from the resale of Cecily Brown’s Faeriefeller (2019) were widely reported [2] and settled on confidential terms. Based on the Conditions of Sale, we understand Huang paid a significant financial settlement to the gallery/artist. We would draw readers attention to the final paragraph of the Gallery’s Conditions of Sale (above) which provided a contractual basis for calculating the money damages payable by Huang on breach. Provisions like this are known as “liquidated damages” clauses. The verb to liquidate means to ‘convert to cash’ and is derived from the Latin verb ‘liquidare’, meaning to make clear. The purpose of a liquidated damages clause is therefore to convert an uncertain future loss into a definite present sum, making the consequences of breach clear to the parties at the time of contracting. The UK Supreme Court reviewed and reformulated the law governing liquidated damages and penalty clauses in a landmark 2015 decision [3], clarifying the circumstances in which such clauses will (and, significantly, will not) be subject to the so-called ‘penalty doctrine’ which can lead to the clause being unenforceable. Whilst the law is complex, the upshot is that contractual resale restrictions can be drafted with “teeth” to incentivise a buyer’s compliance.

The Faeriefeller dispute highlights the discount which buyers on the primary market often receive: Faeriefeller was sold to Huang in December 2019 for USD 700,000 and was resold at Sotheby’s London in March 2022 for GBP 2.9 million (USD 3.9 million) including fees. [4] We understand Sotheby’s commission on this sale alone approached the work’s primary market price of USD 700,000 and, as noted below, the March 2022 sale was in fact the second time a “reputable auction house” had resold the work since Huang’s purchase in late 2019 (the first resale having occurred via private sale in early 2020).

Enforceability under English Law

Resale restrictions are contractual in nature so must meet the formalities of a binding contract to be enforceable. A contract is formed under English law when the following five key elements coincide: offer, acceptance, consideration, intention to create legal relations; and certainty of terms. Art market resale restrictions take a variety of forms ranging from stand-alone documents signed by the buyer (such as the Paula Cooper Gallery’s example above) to concise language on gallery invoices (e.g. “Buyer grants Gallery a Right of First Refusal for Artwork”). Whether a resale restriction satisfies the five key elements will require a case-by-case analysis and no disputes involving the breach of resale restrictions have reached the UK courts at the time of writing (March 2023). Whilst an “agreement to agree” will not bind the parties, the courts seek to preserve rather than destroy bargains. As such, an English court would construe a resale restriction fairly and broadly, without being too astute or subtle in finding defects, recognising that parties “often record important agreements in crude and summary fashion” and that “modes of expression sufficient and clear to them in the course of their business may appear to those unfamiliar with the business far from complete or precise. [5] Whether or not the widespread inclusion of the ‘right of first refusal’ in primary art market transactions makes the term itself sufficiently certain to those in the art business remains a fascinating open question pending a court decision.

Where a resale restriction satisfies the key elements of a binding contract, the English courts will in general enforce the parties agreement under the doctrine of freedom of contract [6]. There are however various circumstances in which the courts may interfere with parties’ freedom of contract [7] and one auction house commentator has suggested that contractual resale restrictions would be “generally likely” to be unenforceable on two specific grounds: either for being (1) “unfair” under the UK’s Consumer Rights Act 2015 when selling to “consumers”; or for being (2) an “unfair restraint of trade” when the buyer is a trader. [8] We consider each ground in turn below and conclude that both have been overstated.

Business-to-Consumer Sales

Where a “trader” (such as an artist or gallery) sells work to a “consumer” (which would catch most if not all collectors), the sale contract will be a “consumer contract” governed by the UK’s Consumer Rights Act 2015 and its terms (including any resale restriction) must be transparent and “fair” to be enforceable. Under section 62 of the CRA, a term will be unfair and unenforceable if, “contrary to the requirement of good faith, it causes a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations under the contract to the detriment of the consumer”. The fairness test is not simply whether the term creates a “significant imbalance” but whether any such imbalance is created “contrary to the requirement of good faith”.

Determining whether a resale restriction creates a “significant imbalance… to the detriment of the consumer” is highly context-specific and the CRA directs parties to consider “the nature of the subject matter of the contract” (so unique artworks will be considered as such) together with “all the circumstances existing when the term was agreed and all of the other terms of the contract.” Relevant factors might therefore include: the knowledge and experience of the buyer (including their familiarity with the art market and resale restrictions); the duration and nature of the resale restriction; the price paid by the buyer; the existence of waiting lists for the artist; and the mechanism for determining the resale price where the artist or gallery has a right of first refusal. Since parties’ commercial interests will usually pull in different directions, the UK courts recognise that rights and obligations can be “incommensurate without being unbalanced”. [9]

“Good faith” in this context requires the artist or gallery to deal fairly and openly with the buyer. [10] To comply with this requirement, resale restrictions should be expressed fully, clearly and transparently in plain English with no hidden traps (not buried in small-print) and appropriate prominence should be given in terms of font size and colour. Whilst the transparency of concise restrictions (e.g. “Buyer grants Gallery a Right of First Refusal for Artwork”) may depend on the knowledge and experience of the particular consumer, providing the consumer with a separate, stand-alone document to read and sign if they agree - as the Paula Cooper Gallery did - may go some way to demonstrating “good faith” under English law. Each case would turn on its facts but we think it highly unlikely that a UK court would find a well-drafted right of first refusal along the lines of the Paula Cooper Gallery’s example to be “unfair” and unenforceable under the CRA.

Business-to-Business Sales

Where a work is sold by an artist or gallery to another art market professional (for example: another gallery, dealer or advisor), consumer law will not apply to the sale contract and the parties are presumed to be the best judges of “fairness”. The UK’s restraint of trade doctrine is one of the few public policy grounds for overriding freedom of contract and is concerned with contracts which sterilise a person’s capacity to exercise their profession or calling, or restrict the work they may do for others. Most of the case law relates to post-termination non-compete provisions in employment contracts or post-completion restrictions in business sale agreements (where the seller agrees not to compete with their former business for a given period). As noted, it has been suggested that resale restrictions would be restraint of trade clauses and, as such, be void and unenforceable under English law unless they protect a legitimate business interest and go no further than reasonably necessary to protect that interest.

We agree that a right of first refusal is a restraint of trade. However, most commercial contracts involve some restraint of trade. If I sell an artwork to Maggie, I’m restrained from trading the same work with Martin. If I appoint Phillips as my exclusive agent to sell a recent painting by Cecily Brown confidentially by private sale, I’m restrained from appointing Sotheby’s to sell the same work for the duration of Phillips’ consignment. Recognising this commercial reality, the UK courts draw a line between contracts in restraint of trade within the meaning of the restraint of trade doctrine, and ordinary contracts that merely regulate the commercial dealings of the parties – even though the latter will usually involve some necessary restraint on the freedom of trade of one or both of the parties. [11] Accordingly, when a party invokes the restraint of trade doctrine, the first question is whether the contract in question is in restraint of trade within the meaning of the doctrine. If it is not, no question of reasonableness arises. Only if the contract in question is in restraint of trade within the meaning of the doctrine does its enforceability become subject to a public policy reasonableness test - in which case it would indeed need to protect a legitimate business interest and go no further than is reasonably necessary to protect that interest to be enforceable. Restraint of trade was the focus of a significant UK art dispute in 2019/20 when the artist Santiago Montoya filed proceedings alleging his representation agreement with the Halcyon Gallery was an unreasonable restraint of trade and unenforceable for the remainder of its 10-year term. [12] The case settled at mediation.

Unlike a representation agreement, we consider it highly unlikely that a resale restriction in the conditions of sale of a single artwork would be considered a restraint of trade within the meaning of the UK’s restraint of trade doctrine. The buyer’s right to sell the work during the agreed period of restriction may be restricted but the individual will remain free throughout the same period to conduct their profession or trade (whatever that may be). The notion that a trade buyer could acquire a work on the primary market (at the primary market price) and seek the court’s assistance to avoid its contractual obligations seems to be precisely the “chicanery” that the UK courts have been alert to for over half a century in applying the restraint of trade doctrine with the requisite caution. [13]

Seller Beware

Owners of artworks subject to resale restrictions may consider selling privately on the understanding that the selling agent and buyer will keep the transaction confidential. In this scenario, the selling agent (whether an auction house, gallery or dealer) risks a claim in tort for inducing or procuring a breach of contract [14]; and the seller risks both legal liability and reputational damage should news of the “secret” deal become public. We mention three recent cases by way of example.

Amedeo Modigliani, Nu Couché au Coussin Bleu (1916)

The long-running dispute between Yves Bouvier and Dmitry Rybolovlev began when Rybolovlev met the leading art advisor Sandy Heller by chance on a holiday to St Barts. Heller’s clients include the collector and hedge-fund manager Steve Cohen who had sold Modigliani’s Nu Couché au Coussin Bleu (1916) in 2011. The sale was conducted privately but there were rumours that Rybolovlev was the purchaser. When Heller mentioned at their chance encounter that they missed the Modigliani, Rybolovlev bit the bullet and asked how much Cohen had sold it for. With Cohen’s permission, Heller confirmed the sale price was USD 93.5 million. Rybolovlev had understood until that point that Bouvier was acting as his agent and adding a 2% fee to the purchase price. Rybolovlev had in fact paid USD 118 million to Bouvier - a 26% mark-up.

Prominent Miami-based US collector Craig Robins filed US proceedings against the David Zwirner Gallery in 2010 after artist Marlene Dumas “blacklisted” him for selling an early work. Robins claimed that his sale of the work through Zwirner had been subject to an oral agreement that the Gallery would never disclose the transaction. Zwirner denied such an agreement had been made verbally or in writing and the proceedings were dismissed. Zwirner noted during the proceedings that whilst an art sale is usually kept confidential during negotiations, once a piece is sold “the new ownership… is as public or private as the new owner wishes to make it.” Whilst a sale agreement with robust confidentiality provisions may give a seller some comfort, they will be placing their public reputation in the hands of their counterparties.

Finally, Michael Huang’s resale of Cecily Brown’s Faeriefeller (2019) spotlights the risk of placing one’s public reputation in the hands of a third party. Huang resold the work to a friend called Federico Castro Debernardi on the same day he signed the Gallery’s terms, adding a modest 10% commission to the price he had paid. The terms of the Huang-Debernardi agreement are below and suggest Huang trusted Debernardi to keep the transaction secret. For example, neither party would reveal Debernardi as the buyer/owner; neither party would discuss or show images of the work to third parties without the other’s consent; neither party would pay/receive commissions to/from any third party connected to the sale or purchase of Faeriefeller without the other’s written consent; and Huang had a right of first refusal to act as Debernardi’s agent for 30-days should he decide to sell.

Huang-Debernardi: Terms of (Re-)Sale

Unfortunately for Huang, Debernardi resold the work via private sale through a “reputable auction house” in early 2020 and only discovered this when the Paula Cooper Gallery threatened legal action seeking damages of USD 500,000 – 1 million for breach of their Conditions of Sale. Highlighting the increasingly firm line taken by leading artists and galleries against buyers who resell too soon [15], the Gallery noted the negative publicity that legal proceedings would generate: "Litigation will result in the details of the transactions being made public along with the identities of those involved. All of your Communications with the Gallery and our staff will become public as well. Given the artist’s profile, media attention can be expected. Your actions and the various statements you have made to us will become widely known.”

Huang chose to settle the Gallery’s claim before it filed legal proceedings against him and it was notably Huang who brought his breach into the public arena by filing proceedings against Debernardi in the Miami County court for breach of contract and reputational damage. Huang claimed at least USD 1,325,000 against Debernardi including USD 25,000 in legal fees and at least USD 1 million for reputational damage. Reading between the lines, the USD 300,000 balance may represent Huang’s settlement with the Paula Cooper Gallery. Huang and Debernardi settled their dispute on confidential terms.

Rounding up

The debate around the enforceability of contractual resale restrictions in the UK and further afield is not new and engages complex legal issues. At their heart sits a tension between freedom of contract on the one hand and property rights on the other. “Art Law” regularly elicits such tensions and the courts are skilled at resolving them when called upon. [16] What is new, however, is the view from certain quarters that contractual resale restrictions would somehow be “struck out” as unenforceable under English law by virtue of the UK’s Consumer Rights Act 2015 or restraint of trade doctrine. Neither argument bears the weight placed upon it in our view and we consider the UK position to be broadly similar to the US: Until a court decision tells us otherwise, resale restrictions seem perfectly capable of being enforceable under English law when drafted correctly.

The art market has powerful non-legal mechanisms for incentivising behaviour and serious buyers think very carefully before jeopardising their primary market access. As the gulf between primary and secondary market pricing increases, so does a buyer’s incentive to resell sooner rather than later. Contractual resale restrictions offer artists and galleries additional protection and sellers considering a resale in breach are well-advised to tread carefully and seek prior legal advice.

Please get in touch for publicly-available pleadings and decisions mentioned above.

Art Law Studio Ltd is a specialist art law firm based at Studio Voltaire in London. This briefing and any information accessed through the links is for information only and does not constitute legal or any other professional advice. Please contact us for legal advice on your particular circumstances.

——————————————————

NOTES

[1] Where a dealer sells work as an artist’s agent, it owes strict fiduciary duties under English law including a duty not to profit from the relationship without the artist’s express consent. To minimise the risk of dispute, artists and galleries are well-advised to consider and agree in advance which is the beneficiary of any pre-emption right and how any resale commission is to be shared (if at all).

[3] Cavendish Square Holding BV v Makdessi; Parking Eye Ltd v Beavis (Consumers’ Association Intervening) [2015] UKSC 67. Linked here.

[4] Lot 11, Sotheby’s ‘The Now’ Evening Auction, 2 March 2022. Linked here.

[5] Hillas and Co Limited v. Arcos Limited [1932] 147 LT 503. Lord Wright at at 514/7. Linked here.

[6] “…the general approach of the common law [is] that parties are free to contract as they please and that the courts will enforce their agreements – pacta sunt servanda.” Cavendish Square Holding BV v Makdessi; Parking Eye Ltd v Beavis (Consumers’ Association Intervening) [2015] UKSC 67. Lord Hodge at para 257. Linked at Note 3.

[7] For example, where an agreement’s subject matter is illegal or the formation was affected by duress, undue influence, misrepresentation or mistake.

[8] Martin Wilson, ‘Non-Resale Clauses in Art Sales’, Linked-In, (5 Nov. 2020). Linked here.

[9] Deutsche Bank Suisse SA v Khan and others [2013] EWHC 482 (Comm) Para 381. Linked here.

[10] Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank Plc [2001] UKHL 52 Para 17. Linked here.

[11] Quantum Advisory Limited v Quantum Actuarial LLP [2020] EWHC 1072 (Comm) Para 62. Linked here.

[13] “… it might be argued that the court can investigate the reasonableness of any… contract and allow the contracting party to resile subsequently from any bargain which it considers an unreasonable restraint upon his liberty of trade with others. But so wide a power of potential investigation would allow to would-be recalcitrants a wide field of chicanery and delaying tactics in the courts.” Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Harper's Garage (Stourport) Ltd [1968] AC 269. Lord Pearce at page 20. Linked here.

[14] In determining whether a defendant has the requisite knowledge for inducing or procuring a breach of contract, the UK’s highest court has confirmed that knowledge of a fact includes a reckless or wilful failure to make enquiries. As such, wilful blindness by a defendant auction house/agent (e.g. for failing to obtain and review the terms of sale; or failing to make enquiries with the artist or gallery from which a recently executed work was acquired) may not shield it from liability. See OBG Ltd and others v Allan and others [2007] UKHL 21, Lord Hoffmann at paragraphs 40-41; Lord Nicholls at paragraph 192. Linked here.

[15] David Zwirner Gallery provided the art press with the name of a Japanese collector in 2019 who consigned two works to Sotheby’s within a year of purchase; and Anton Kern Gallery named the US collector who consigned a Julie Curtiss work to Sotheby’s in 2020.

[16] For example: freedom of expression v. the right to privacy (see Jomeen, A. "Street Photography in New York and Paris: A Comparative Legal Analysis." Art Antiquity & Law, vol. 24, no. 4, Dec. 2019, pp. 295+. Linked here); freedom of expression v. property rights (which go to the heart of copyright disputes such as Warhol v. Goldsmith which awaits the decision of the US Supreme Court); and property rights v. property rights (for example, the long-running US dispute over ownership of a Nazi-looted painting by Camille Pissarro currently in the collection of Spain’s State-owned Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection. The Institute of Art & Law’s excellent reporting is linked here).

Warhol v Goldsmith: All’s fair in Art & War?

As the dispute between the Warhol Foundation and Lynn Goldsmith reaches the US Supreme Court, we consider the road to Washington and the issues at stake

Last week the United States’ Supreme Court heard oral argument in The Andy Warhol Foundation v Lynn Goldsmith - a copyright dispute over what is (and is not) permitted under the US doctrine of “fair use”. Given the case’s potential impact on the market for certain art works by Warhol and other artists who appropriate the work of others without permission, it was somewhat fitting that the hearing before the nine US Supreme Court Justices at 10AM Eastern Time on 12 October 2022 coincided with the VIP previews of Frieze in London – where several Warhol works hung above the hallowed turf of Regent’s Park.

Once bitten

Warhol did not initially seek permission from the brands or photographers whose work he immortalised through his silkscreen process. As a result, he was sued for copyright infringement at least three times in the US courts during his lifetime by the creators of the source imagery in his now iconic Flowers (1964), Race Riot (1964) and Jackie Kennedy (1966) works. Those three claims were settled out of court, but they placed copyright firmly on Warhol's radar from 1966 - when he was sued by Patricia Caulfield - and he began taking his own photographs or securing licenses from the source photographers to mitigate legal risk.

Prince Rogers Nelson (aka/fka “Prince”), photographed by Lynn Goldsmith (1981)

‘Purple Fame’

Fast-forward to 1984. Vanity Fair magazine was preparing a feature on the musician then-known as Prince whose ‘Purple Rain’ album was the talk of the town. The article would be titled ‘Purple Fame’ and the magazine approached the acclaimed artist-photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s licensing agency for a one-off permission to use her 1981 image of Prince as an artist reference. An artist reference allows another artist to create a derivative work based on Goldsmith’s portrait.

Extract of licence issued by Goldsmith’s agency to Vanity Fair. Note deletion of “or reproduce”.

Goldsmith’s agency issued a well-drafted licence (partly shown above) to the magazine specifying the parameters of its permission and charged a USD 400 licensing fee. Vanity Fair did not - and was not required to - inform Goldsmith that the artist they had commissioned was Andy Warhol. Vanity Fair published its piece on Prince in November 1984 – illustrated by Warhol’s “Purple Prince” – and Goldsmith was credited as the image source as required by the licence.

Vanity Fair’s 1984 “Purple Fame” article and accompanying Warhol illustration of Prince. (Source: US Court Documents)

Creative licence

Unbeknownst to Goldsmith – and apparently remaining unknown to her until Prince’s death in 2016 – Warhol did not stop with the “Purple Prince” commission. Instead, he created 16 works in a variety of colour-ways which together comprise his “Prince Series”.

Warhol’s 16-work Prince Series. (Source: US Court Documents)

On Prince’s death in 2016, Condé Nast published a special commemorative edition with Warhol’s “Orange Prince” on the cover – which Goldsmith had neither seen nor authorised. Condé Nast had obtained a license from The Warhol Foundation to use “Orange Prince” - and paid a USD 10,000 licence fee to the Foundation. Goldsmith received no payment or image credit. Not unreasonably, Goldsmith argues that by licensing works from the Prince Series to illustrate articles about Prince (not Warhol), the Foundation is competing in the same licensing market as her 1981 photograph of Prince.

The 2016 Condé Nast magazine cover and Goldsmith’s 1981 Prince Photograph.

Goldsmith notified the Foundation of its apparent violation of her copyright in the Prince photo and threatened legal action if an agreement could not be reached. Turning defence into attack, the Foundation filed proceedings in 2017 against Goldsmith before the New York District Court seeking a declaratory judgment that Warhol’s Prince Series works were non-infringing or, in the alternative, that they made “fair use” of Goldsmith’s photograph. Goldsmith and her agency counter-claimed for copyright infringement.

Road to the Supreme Court

The 1st Instance District Court ruled in 2019 that Warhol’s use was permitted “fair use” – meaning Warhol had not committed copyright infringement. Goldsmith appealed to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, which is probably the most important US federal appeals court for copyright cases since it hears appeals from New York. The Second Circuit ruled decisively in Goldsmith’s favour in March 2021, overturning the District Court and finding Warhol’s use was not fair. The Warhol Foundation petitioned the Supreme Court to hear its appeal in late 2021 and permission was granted in March 2022. Given that the US Supreme Court rejects almost all of the cases it is asked to review each year - it accepts just 100-150 appeals from over 7,000 petitions – and has never heard a fair use case involving the visual arts, art lawyers and the wider art world await the decision with breath that is bated.

Copyright law in context

In general, copyright regimes around the world seek to incentivise creativity by granting creators exclusive rights to copy and profit economically from their qualifying works – and to prevent others from doing so – for a limited period. Like some artistic mediums, that requires the drawing of lines. The dividing line between acceptable taking and illegal copyright infringement depends on the jurisdiction and, by international standards, the US “fair use” doctrine provides the greatest scope for artists to legally use the work of others without permission. This is consistent with the primacy given to freedom of speech in the United States as enshrined in the First Amendment to the US Constitution and it is no coincidence that the most well-known appropriation artists are (or were) Americans working in the US.

SUPERFLEX, I Copy Therefore I Am (2011) - altering Barbara Kruger’s 1987 iconic print work Untitled (I shop therefore I am).

Amicus “Friend of the Court” briefs supporting the Warhol Foundation were filed by artists including Barbara Kruger - who makes no secret of her antipathy to copyright - and the Robert Rauschenberg and Roy Lichtenstein Foundations. Whilst potentially more permissive than copyright regimes in Europe and the UK, the US fair use doctrine is notoriously unpredictable and decisions are regularly overturned on appeal – as the current Warhol v Goldsmith dispute illustrates.

“Fair use” under US law

To assess whether a challenged use of a copyrighted work - such as Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photograph - is “fair”, US courts are required to consider the following four non-exclusive statutory factors contained at Section 107 of the US Copyright Act 1976:

the purpose and character of the use, including whether the use is commercial or for non-profit educational purposes;

the nature of the copyrighted work;

the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole;

the effect of the use on the potential market for, or value of, the copyrighted work.

Highlighting the doctrine’s unpredictable nature, the District Court considered all four fair use factors favoured the Warhol Foundation; and the Second Circuit Appeal Court considered all four factors favoured Goldsmith.

Is it transformative?

Whilst the US Copyright Act requires a holistic balancing of all four fair use factors, the US Supreme Court muddied the waters in 1994 by introducing the concept of “transformativeness” in a landmark fair use decision involving a music parody of the Pretty Woman theme song.

Building on a 1990 Harvard Law Review article by respected Judge Pierre Laval, the Supreme Court held in its Pretty Woman opinion that a challenged work would be “transformative” if it:

“adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the [appropriated work] with new expression, meaning, or message… the more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use.”

Since that decision, US courts have gradually expanded the application of “transformativeness” such that it has become a litmus test for fair use – particularly in claims relating to appropriation art – swallowing the other factors. Nowhere is this expansion more evident than a 2013 decision involving another Prince - this time the renowned artist Richard Prince.

Cariou v. Prince

In Cariou v. Prince, the Second Circuit Appeal Court held that 25 of 30 contested works by Richard Prince were entitled to a fair use defence because they were transformative. Richard Prince had taken images he found in Patrick Cariou’s Yes Rasta book and incorporated these in various guises into his Canal Zone series (named after The Panama Canal Zone where he was born). In reaching its decision, the Second Circuit overturned the lower court’s decision which had ruled against Richard Prince and his gallery Gagosian.

Richard Prince, The Canal Zone, 2007

Celebrity-plagiarist privilege?

Three years later - in a 2016 decision - the Second Circuit acknowledged criticism of its ruling in Cariou v. Prince and said that decision represented the “high-water mark of our court’s recognition of transformative works”. In what some consider to be a further rowing-back from said high-water mark, the Second Circuit’s 2021 ruling in Warhol v Goldsmith said:

Finally, we feel compelled to clarify that it is entirely irrelevant… that “each Prince Series work is… recognizable as a ‘Warhol.’” … Entertaining that logic would inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege; the more established the artist and the more distinct that artist’s style, the greater leeway that artist would have to pilfer the creative labors of others. But the law draws no such distinctions; whether the Prince Series images exhibit the style and characteristics typical of Warhol’s work (which they do) does not bear on whether they qualify as fair use under the Copyright Act.

Looking ahead

It is to be hoped that the US Supreme Court will provide guidance on when a work is (and is not) “transformative” – and what that means in the context of the other fair use factors. The decision is expected in the coming months. In the meantime, the recording of the oral argument and transcript make for fascinating listening and reading and are available here.

[1] Cariou v. Prince, 714 F. 3d 694 (2d Cir. 2013)

[2] TCA Television Corp. v. McCollum, 839 F.3d 168, 181 (2d Cir. 2016)

This briefing and any information accessed through the links is for information only and does not constitute legal advice. Please contact us for legal advice on your particular circumstances.

NFTs, Joint Authorship and Artist-Dealer Disputes

Christopher Hartmann, Untitled (No. 3), 2022. Oil on linen. 140x105cm. © 2022 Christopher Hartmann. Courtesy the artist, Nassima Landau, Art Intelligence Global and T&Y Projects.

We report recent art law developments from the around the world with insights from our practice

Damien Hirst’s first non-fungible token (NFT) initiative – wryly titled The Currency – comprised 10,000 NFTs, each corresponding to one of 10,000 similar but unique spot works on handmade A4 paper created in 2016. Launched in July 2021 at a primary price of USD 2,000 per NFT (payable in fiat or crypto currency), Hirst gave collectors a choice: keep the NFT and burn the corresponding physical work; or “burn” the NFT and receive the work on paper. The exchange period closed at 3pm GMT on 27 July 2022 and The Currency’s final composition has been confirmed: 5,149 physical works and 4,851 NFTs.

Totally gonna sell you: The Currency’s final composition of NFTs and Physicals.

As the art market’s appetite for NFTs has perhaps inevitably cooled since the extraordinary US69M Beeple sale in March 2020, the choice may have been harder for some than others. We were monitoring the final stages and over 1,000 NFTs were exchanged for physical artwork in the last 24 hours. Hirst disclosed on Instagram that he holds 10% of The Currency and decided at the last moment to keep all 1,000 as NFTs “to show my 100 percent support and confidence in the NFT world”. Stripping-out Hirst’s 10% momentarily, the public choice was accordingly 5,149 physical works and 3,851 NFTs - or a 57%/43% split. Including Hirst’s holding, the near 50/50 split should allow markets for the NFTs and “Physicals” to develop and it will be interesting to track prices and confidence in each medium now edition numbers are concretised.

Currency by name: this “Physical” recently sold at auction for €47,880

Hirst will be exhibiting the 4,851 works on paper marked for destruction at his Newport Street Gallery from 9 September 2022 and burning (cue: nervous art lawyers) a selection each day until the exhibition closes during Frieze week in mid-October. As Hirst put it in an interview with Stephen Fry: “The whole thing is the artwork”.

Maurizio Cattelan, La Nona Ora (The Ninth Hour), 1999. Mark B. Schlemmer CC BY 2.0.

Crossing the Channel, we recently reported on the proceedings filed in the Paris courts by Daniel Druet - the artist-sculptor commissioned by Maurizio Cattelan and his gallery (Perrotin) to produce nine hyper-realistic wax sculptures which Cattelan incorporated into some of his most famous and highly valued works including La Nona Ora (1999) – shown above featuring Pope Jean Paul II felled by an errant meteor – and Him (2001) portraying a penitent, kneeling Adolf Hitler with child’s body. Produced in an edition of 3 + 1 Artist’s Proof, the AP of Him sold for USD17.2M at Christie’s Bound to Fail sale masterminded by Loïc Gouzer in May 2016. It remains Cattelan’s auction record.

From its Renzo Piano-designed HQ, the Paris Judicial Court’s 3rd Chamber - which specialises in intellectual property disputes - rendered its decision on 8 July 2022. The Court noted that pursuant to article L. 113-1 of the French Intellectual Property Code, the person in whose name an artwork is disclosed to the public is the presumptive author. Since all nine contested works were disclosed to the public in Cattelan’s name, the starting point under French law is that Cattelan is the sole author and it is for Druet to overturn the presumption. Druet filed his proceedings against three French parties: (a) Perrotin; (b) Perrotin’s publishing company, Turenne Editions; and (c) the museum Monnaie de Paris which exhibited four of the disputed works in its 2016/17 show “Maurizio Cattelan: Not Afraid of Love” without crediting Druet. Whilst Cattelan was joined to the proceedings by the museum as a forced intervener under a contractual indemnity, he was not included as a primary defendant by Druet. Since Druet’s claims against the three defendants depend on him proving that he is sole author of the disputed works to Cattelan’s detriment, the Court considered it essential that Cattelan - as the presumptive copyright owner - also be called as a primary defendant by Druet. Absent Cattelan, the Court ruled Druet’s claims were “inadmissible”.

Across the courtyard on the right: La galerie Perrotin at 76 Rue de Turenne

So what does this all mean in practice? Emmanuel Perrotin has said the decision rejects “in every respect the inadmissible and unfounded arguments of Daniel Druet” and “puts an end to this controversy which has threatened a large number of contemporary artists”. As others have noted, this is an optimistic analysis since the Court has yet to consider the key intellectual property question of whether Druet has IP rights in the wax effigies and/or the final works. The Court noted that by framing his claim around the titles of the nine works, Druet was effectively claiming sole ownership of the final artworks as they were staged and disclosed to the public by Cattelan. It remains to be seen whether Druet will now include Cattelan as a defendant and reframe his claim seeking joint (rather than sole) authorship.

Götz Valien, "Paris Bar", Variante 3, 1993–2010

On the subject of joint authorship, we recently reported on the “Paris Bar” paintings which Martin Kippenberger commissioned Götz Valien to paint in 1991 and 1993. Valien made an identical version of the 1991 work in 2010 which he attributed to himself (alone), raising the question of whether the 2010 work infringed copyright in the 1991 work.

We thought it unlikely that the Kippenberger Estate would bring proceedings against Valien. In fact, the opposite has occurred: Valien filed proceedings this month in the Copyright Chamber of Munich’s Regional Court against the Kippenberger Estate which manages Kippenberger’s copyright estate and publishes the artist’s catalogue raisonné. The action seeks to prevent the Estate from exploiting the “Paris Bar” paintings without naming Götz Valien as co-author. Highlighting the art world’s global nature, the press release from Valien’s German lawyers cites the Druet/Cattelan dispute as evidence of “the bad habit… among conceptual artists of refusing to recognize the co-authorship of the actual creators of their works.” We are following the proceedings with our German correspondents with interest.