On the Flip Side: Resale Restrictions under English Law

The Last Supper (detail), c.1515-1520. Attributed to Giampietrino (fl. 1508-1549) and Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio (1467 - 1516). Copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, 1494-1498.

As the gap between primary and secondary market pricing widens, we look at the use and enforceability of contractual resale restrictions under English law.

Coming to an Evening Sale near you

The art market’s appetite for increasingly wet paintings continued unabated in 2022 with striking auction debuts for artists including Lucy Bull (b.1990), Anna Park (b.1996) and Lauren Quin (b.1992). Bull’s ‘8:50’ (2020) sold for USD 1.45 million at Phillips Hong Kong; Quin’s ‘Airsickness’ (2021) sold for USD 587,000 at Phillips London; and - with the question on everyone’s lips, perhaps - Park’s ‘Is it worth it?’ (2020) sold for USD 480,000 at Christie’s Hong Kong. And building on a remarkable 2021 in which auction prices passed USD 1 million in June and GBP 2 million in October, the market for British painter Flora Yukhnovich (b.1990) showed little sign of cooling in 2022.

The pricing gap between the primary market (by which we mean the first sale of a new work - either directly from the artist or through their gallery) and the secondary market (every subsequent re-sale) can be striking. Yukhnovich’s large-scale paintings were reportedly priced at around USD 40,000 in 2019. The artist showed new work with the Victoria Miro in March 2022 where the largest works were reportedly priced at GBP 350,000 (USD 470,000). The same month, a work executed in 2020 achieved GBP 2.7 million (USD 3.6 million) at Sotheby’s in London.

Since the goal of artists and their dealers is not usually to secure the highest price but to place work in private and public collections which enhance the artist’s profile and offer the work critical exposure over the long-term, a speculative market presents artists and their dealers with a number of interconnected challenges, not least: deciding the level at which to price new work; deciding who is given primary market access at an effective discount to “market” (if that word captures the price that the highest bidder would be willing to pay); and deciding what mechanisms will be relied on to incentivise buyers to hold the work rather than take it straight to auction.

Contractual Resale Restrictions

One increasingly utilised legal tool - and the focus of this briefing - is the contractual resale restriction which typically restricts the buyer’s ability to resell or otherwise dispose of a work for a specified period. The most common restriction is a “pre-emption right” or “right of first refusal” which usually requires the buyer to offer the work back to the artist or gallery if they wish to resell within an agreed period after purchase (typically 3 to 5 years). Where the gallery acts as the buyer’s resale agent under a right of first refusal, it will earn a commission on the resale which it may have agreed to share with the artist (adding to the limited artist resale right available to certain artists in certain jurisdictions including the UK). [1]

Contractual resale restrictions were at the heart of a recent US dispute between the Paula Cooper Gallery and the high-profile Chinese museum founder Michael Xufu Huang who resold Cecily Brown’s Faeriefeller (2019) in breach of the Gallery’s Conditions of Sale which included a pre-emption right. Huang signed the Conditions of Sale and later filed a copy in Florida court proceedings (see below):

Paula Cooper Gallery’s Conditions of Sale signed by Michael Xufu Huang on 4 December 2019. Filed with the Florida Court by Huang in his claim against Federico Castro Debernardi (Case No.: 2021-005156-CA-01).

The disputes arising from the resale of Cecily Brown’s Faeriefeller (2019) were widely reported [2] and settled on confidential terms. Based on the Conditions of Sale, we understand Huang paid a significant financial settlement to the gallery/artist. We would draw readers attention to the final paragraph of the Gallery’s Conditions of Sale (above) which provided a contractual basis for calculating the money damages payable by Huang on breach. Provisions like this are known as “liquidated damages” clauses. The verb to liquidate means to ‘convert to cash’ and is derived from the Latin verb ‘liquidare’, meaning to make clear. The purpose of a liquidated damages clause is therefore to convert an uncertain future loss into a definite present sum, making the consequences of breach clear to the parties at the time of contracting. The UK Supreme Court reviewed and reformulated the law governing liquidated damages and penalty clauses in a landmark 2015 decision [3], clarifying the circumstances in which such clauses will (and, significantly, will not) be subject to the so-called ‘penalty doctrine’ which can lead to the clause being unenforceable. Whilst the law is complex, the upshot is that contractual resale restrictions can be drafted with “teeth” to incentivise a buyer’s compliance.

The Faeriefeller dispute highlights the discount which buyers on the primary market often receive: Faeriefeller was sold to Huang in December 2019 for USD 700,000 and was resold at Sotheby’s London in March 2022 for GBP 2.9 million (USD 3.9 million) including fees. [4] We understand Sotheby’s commission on this sale alone approached the work’s primary market price of USD 700,000 and, as noted below, the March 2022 sale was in fact the second time a “reputable auction house” had resold the work since Huang’s purchase in late 2019 (the first resale having occurred via private sale in early 2020).

Enforceability under English Law

Resale restrictions are contractual in nature so must meet the formalities of a binding contract to be enforceable. A contract is formed under English law when the following five key elements coincide: offer, acceptance, consideration, intention to create legal relations; and certainty of terms. Art market resale restrictions take a variety of forms ranging from stand-alone documents signed by the buyer (such as the Paula Cooper Gallery’s example above) to concise language on gallery invoices (e.g. “Buyer grants Gallery a Right of First Refusal for Artwork”). Whether a resale restriction satisfies the five key elements will require a case-by-case analysis and no disputes involving the breach of resale restrictions have reached the UK courts at the time of writing (March 2023). Whilst an “agreement to agree” will not bind the parties, the courts seek to preserve rather than destroy bargains. As such, an English court would construe a resale restriction fairly and broadly, without being too astute or subtle in finding defects, recognising that parties “often record important agreements in crude and summary fashion” and that “modes of expression sufficient and clear to them in the course of their business may appear to those unfamiliar with the business far from complete or precise. [5] Whether or not the widespread inclusion of the ‘right of first refusal’ in primary art market transactions makes the term itself sufficiently certain to those in the art business remains a fascinating open question pending a court decision.

Where a resale restriction satisfies the key elements of a binding contract, the English courts will in general enforce the parties agreement under the doctrine of freedom of contract [6]. There are however various circumstances in which the courts may interfere with parties’ freedom of contract [7] and one auction house commentator has suggested that contractual resale restrictions would be “generally likely” to be unenforceable on two specific grounds: either for being (1) “unfair” under the UK’s Consumer Rights Act 2015 when selling to “consumers”; or for being (2) an “unfair restraint of trade” when the buyer is a trader. [8] We consider each ground in turn below and conclude that both have been overstated.

Business-to-Consumer Sales

Where a “trader” (such as an artist or gallery) sells work to a “consumer” (which would catch most if not all collectors), the sale contract will be a “consumer contract” governed by the UK’s Consumer Rights Act 2015 and its terms (including any resale restriction) must be transparent and “fair” to be enforceable. Under section 62 of the CRA, a term will be unfair and unenforceable if, “contrary to the requirement of good faith, it causes a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations under the contract to the detriment of the consumer”. The fairness test is not simply whether the term creates a “significant imbalance” but whether any such imbalance is created “contrary to the requirement of good faith”.

Determining whether a resale restriction creates a “significant imbalance… to the detriment of the consumer” is highly context-specific and the CRA directs parties to consider “the nature of the subject matter of the contract” (so unique artworks will be considered as such) together with “all the circumstances existing when the term was agreed and all of the other terms of the contract.” Relevant factors might therefore include: the knowledge and experience of the buyer (including their familiarity with the art market and resale restrictions); the duration and nature of the resale restriction; the price paid by the buyer; the existence of waiting lists for the artist; and the mechanism for determining the resale price where the artist or gallery has a right of first refusal. Since parties’ commercial interests will usually pull in different directions, the UK courts recognise that rights and obligations can be “incommensurate without being unbalanced”. [9]

“Good faith” in this context requires the artist or gallery to deal fairly and openly with the buyer. [10] To comply with this requirement, resale restrictions should be expressed fully, clearly and transparently in plain English with no hidden traps (not buried in small-print) and appropriate prominence should be given in terms of font size and colour. Whilst the transparency of concise restrictions (e.g. “Buyer grants Gallery a Right of First Refusal for Artwork”) may depend on the knowledge and experience of the particular consumer, providing the consumer with a separate, stand-alone document to read and sign if they agree - as the Paula Cooper Gallery did - may go some way to demonstrating “good faith” under English law. Each case would turn on its facts but we think it highly unlikely that a UK court would find a well-drafted right of first refusal along the lines of the Paula Cooper Gallery’s example to be “unfair” and unenforceable under the CRA.

Business-to-Business Sales

Where a work is sold by an artist or gallery to another art market professional (for example: another gallery, dealer or advisor), consumer law will not apply to the sale contract and the parties are presumed to be the best judges of “fairness”. The UK’s restraint of trade doctrine is one of the few public policy grounds for overriding freedom of contract and is concerned with contracts which sterilise a person’s capacity to exercise their profession or calling, or restrict the work they may do for others. Most of the case law relates to post-termination non-compete provisions in employment contracts or post-completion restrictions in business sale agreements (where the seller agrees not to compete with their former business for a given period). As noted, it has been suggested that resale restrictions would be restraint of trade clauses and, as such, be void and unenforceable under English law unless they protect a legitimate business interest and go no further than reasonably necessary to protect that interest.

We agree that a right of first refusal is a restraint of trade. However, most commercial contracts involve some restraint of trade. If I sell an artwork to Maggie, I’m restrained from trading the same work with Martin. If I appoint Phillips as my exclusive agent to sell a recent painting by Cecily Brown confidentially by private sale, I’m restrained from appointing Sotheby’s to sell the same work for the duration of Phillips’ consignment. Recognising this commercial reality, the UK courts draw a line between contracts in restraint of trade within the meaning of the restraint of trade doctrine, and ordinary contracts that merely regulate the commercial dealings of the parties – even though the latter will usually involve some necessary restraint on the freedom of trade of one or both of the parties. [11] Accordingly, when a party invokes the restraint of trade doctrine, the first question is whether the contract in question is in restraint of trade within the meaning of the doctrine. If it is not, no question of reasonableness arises. Only if the contract in question is in restraint of trade within the meaning of the doctrine does its enforceability become subject to a public policy reasonableness test - in which case it would indeed need to protect a legitimate business interest and go no further than is reasonably necessary to protect that interest to be enforceable. Restraint of trade was the focus of a significant UK art dispute in 2019/20 when the artist Santiago Montoya filed proceedings alleging his representation agreement with the Halcyon Gallery was an unreasonable restraint of trade and unenforceable for the remainder of its 10-year term. [12] The case settled at mediation.

Unlike a representation agreement, we consider it highly unlikely that a resale restriction in the conditions of sale of a single artwork would be considered a restraint of trade within the meaning of the UK’s restraint of trade doctrine. The buyer’s right to sell the work during the agreed period of restriction may be restricted but the individual will remain free throughout the same period to conduct their profession or trade (whatever that may be). The notion that a trade buyer could acquire a work on the primary market (at the primary market price) and seek the court’s assistance to avoid its contractual obligations seems to be precisely the “chicanery” that the UK courts have been alert to for over half a century in applying the restraint of trade doctrine with the requisite caution. [13]

Seller Beware

Owners of artworks subject to resale restrictions may consider selling privately on the understanding that the selling agent and buyer will keep the transaction confidential. In this scenario, the selling agent (whether an auction house, gallery or dealer) risks a claim in tort for inducing or procuring a breach of contract [14]; and the seller risks both legal liability and reputational damage should news of the “secret” deal become public. We mention three recent cases by way of example.

Amedeo Modigliani, Nu Couché au Coussin Bleu (1916)

The long-running dispute between Yves Bouvier and Dmitry Rybolovlev began when Rybolovlev met the leading art advisor Sandy Heller by chance on a holiday to St Barts. Heller’s clients include the collector and hedge-fund manager Steve Cohen who had sold Modigliani’s Nu Couché au Coussin Bleu (1916) in 2011. The sale was conducted privately but there were rumours that Rybolovlev was the purchaser. When Heller mentioned at their chance encounter that they missed the Modigliani, Rybolovlev bit the bullet and asked how much Cohen had sold it for. With Cohen’s permission, Heller confirmed the sale price was USD 93.5 million. Rybolovlev had understood until that point that Bouvier was acting as his agent and adding a 2% fee to the purchase price. Rybolovlev had in fact paid USD 118 million to Bouvier - a 26% mark-up.

Prominent Miami-based US collector Craig Robins filed US proceedings against the David Zwirner Gallery in 2010 after artist Marlene Dumas “blacklisted” him for selling an early work. Robins claimed that his sale of the work through Zwirner had been subject to an oral agreement that the Gallery would never disclose the transaction. Zwirner denied such an agreement had been made verbally or in writing and the proceedings were dismissed. Zwirner noted during the proceedings that whilst an art sale is usually kept confidential during negotiations, once a piece is sold “the new ownership… is as public or private as the new owner wishes to make it.” Whilst a sale agreement with robust confidentiality provisions may give a seller some comfort, they will be placing their public reputation in the hands of their counterparties.

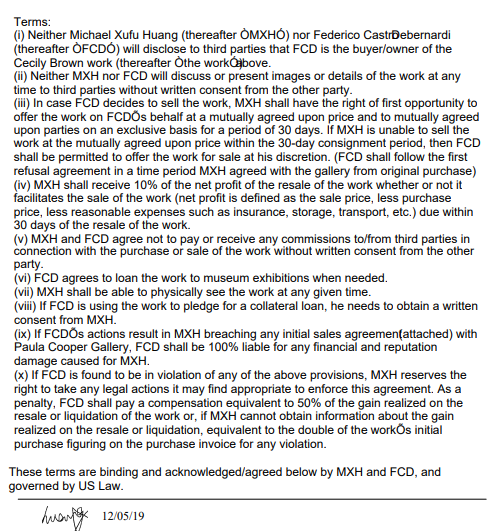

Finally, Michael Huang’s resale of Cecily Brown’s Faeriefeller (2019) spotlights the risk of placing one’s public reputation in the hands of a third party. Huang resold the work to a friend called Federico Castro Debernardi on the same day he signed the Gallery’s terms, adding a modest 10% commission to the price he had paid. The terms of the Huang-Debernardi agreement are below and suggest Huang trusted Debernardi to keep the transaction secret. For example, neither party would reveal Debernardi as the buyer/owner; neither party would discuss or show images of the work to third parties without the other’s consent; neither party would pay/receive commissions to/from any third party connected to the sale or purchase of Faeriefeller without the other’s written consent; and Huang had a right of first refusal to act as Debernardi’s agent for 30-days should he decide to sell.

Huang-Debernardi: Terms of (Re-)Sale

Unfortunately for Huang, Debernardi resold the work via private sale through a “reputable auction house” in early 2020 and only discovered this when the Paula Cooper Gallery threatened legal action seeking damages of USD 500,000 – 1 million for breach of their Conditions of Sale. Highlighting the increasingly firm line taken by leading artists and galleries against buyers who resell too soon [15], the Gallery noted the negative publicity that legal proceedings would generate: "Litigation will result in the details of the transactions being made public along with the identities of those involved. All of your Communications with the Gallery and our staff will become public as well. Given the artist’s profile, media attention can be expected. Your actions and the various statements you have made to us will become widely known.”

Huang chose to settle the Gallery’s claim before it filed legal proceedings against him and it was notably Huang who brought his breach into the public arena by filing proceedings against Debernardi in the Miami County court for breach of contract and reputational damage. Huang claimed at least USD 1,325,000 against Debernardi including USD 25,000 in legal fees and at least USD 1 million for reputational damage. Reading between the lines, the USD 300,000 balance may represent Huang’s settlement with the Paula Cooper Gallery. Huang and Debernardi settled their dispute on confidential terms.

Rounding up

The debate around the enforceability of contractual resale restrictions in the UK and further afield is not new and engages complex legal issues. At their heart sits a tension between freedom of contract on the one hand and property rights on the other. “Art Law” regularly elicits such tensions and the courts are skilled at resolving them when called upon. [16] What is new, however, is the view from certain quarters that contractual resale restrictions would somehow be “struck out” as unenforceable under English law by virtue of the UK’s Consumer Rights Act 2015 or restraint of trade doctrine. Neither argument bears the weight placed upon it in our view and we consider the UK position to be broadly similar to the US: Until a court decision tells us otherwise, resale restrictions seem perfectly capable of being enforceable under English law when drafted correctly.

The art market has powerful non-legal mechanisms for incentivising behaviour and serious buyers think very carefully before jeopardising their primary market access. As the gulf between primary and secondary market pricing increases, so does a buyer’s incentive to resell sooner rather than later. Contractual resale restrictions offer artists and galleries additional protection and sellers considering a resale in breach are well-advised to tread carefully and seek prior legal advice.

Please get in touch for publicly-available pleadings and decisions mentioned above.

Art Law Studio Ltd is a specialist art law firm based at Studio Voltaire in London. This briefing and any information accessed through the links is for information only and does not constitute legal or any other professional advice. Legal advice on your particular circumstances should be sought before taking or refraining from any action.

——————————————————

NOTES

[1] Where a dealer sells work as an artist’s agent, it owes strict fiduciary duties under English law including a duty not to profit from the relationship without the artist’s express consent. To minimise the risk of dispute, artists and galleries are well-advised to consider and agree in advance which is the beneficiary of any pre-emption right and how any resale commission is to be shared (if at all).

[3] Cavendish Square Holding BV v Makdessi; Parking Eye Ltd v Beavis (Consumers’ Association Intervening) [2015] UKSC 67. Linked here.

[4] Lot 11, Sotheby’s ‘The Now’ Evening Auction, 2 March 2022. Linked here.

[5] Hillas and Co Limited v. Arcos Limited [1932] 147 LT 503. Lord Wright at at 514/7. Linked here.

[6] “…the general approach of the common law [is] that parties are free to contract as they please and that the courts will enforce their agreements – pacta sunt servanda.” Cavendish Square Holding BV v Makdessi; Parking Eye Ltd v Beavis (Consumers’ Association Intervening) [2015] UKSC 67. Lord Hodge at para 257. Linked at Note 3.

[7] For example, where an agreement’s subject matter is illegal or the formation was affected by duress, undue influence, misrepresentation or mistake.

[8] Martin Wilson, ‘Non-Resale Clauses in Art Sales’, Linked-In, (5 Nov. 2020). Linked here.

[9] Deutsche Bank Suisse SA v Khan and others [2013] EWHC 482 (Comm) Para 381. Linked here.

[10] Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank Plc [2001] UKHL 52 Para 17. Linked here.

[11] Quantum Advisory Limited v Quantum Actuarial LLP [2020] EWHC 1072 (Comm) Para 62. Linked here.

[13] “… it might be argued that the court can investigate the reasonableness of any… contract and allow the contracting party to resile subsequently from any bargain which it considers an unreasonable restraint upon his liberty of trade with others. But so wide a power of potential investigation would allow to would-be recalcitrants a wide field of chicanery and delaying tactics in the courts.” Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Harper's Garage (Stourport) Ltd [1968] AC 269. Lord Pearce at page 20. Linked here.

[14] In determining whether a defendant has the requisite knowledge for inducing or procuring a breach of contract, the UK’s highest court has confirmed that knowledge of a fact includes a reckless or wilful failure to make enquiries. As such, wilful blindness by a defendant auction house/agent (e.g. for failing to obtain and review the terms of sale; or failing to make enquiries with the artist or gallery from which a recently executed work was acquired) may not shield it from liability. See OBG Ltd and others v Allan and others [2007] UKHL 21, Lord Hoffmann at paragraphs 40-41; Lord Nicholls at paragraph 192. Linked here.

[15] David Zwirner Gallery provided the art press with the name of a Japanese collector in 2019 who consigned two works to Sotheby’s within a year of purchase; and Anton Kern Gallery named the US collector who consigned a Julie Curtiss work to Sotheby’s in 2020.

[16] For example: freedom of expression v. the right to privacy (see Jomeen, A. "Street Photography in New York and Paris: A Comparative Legal Analysis." Art Antiquity & Law, vol. 24, no. 4, Dec. 2019, pp. 295+. Linked here); freedom of expression v. property rights (which go to the heart of copyright disputes such as Warhol v. Goldsmith which awaits the decision of the US Supreme Court); and property rights v. property rights (for example, the long-running US dispute over ownership of a Nazi-looted painting by Camille Pissarro currently in the collection of Spain’s State-owned Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection. The Institute of Art & Law’s excellent reporting is linked here).